I try not to write fiction that requires footnotes, but maybe “Walther PKD” does. It’s one of the oddest stories I’ve ever written.

I try not to write fiction that requires footnotes, but maybe “Walther PKD” does. It’s one of the oddest stories I’ve ever written.

On January 4th of this year I slipped on ice while trying to shovel snow off my steep-ish driveway. I broke my left arm at the shoulder joint. For two weeks I endured intense pain, unable to lie down to sleep, propping myself up on the couch or bed like John Hurt in The Elephant Man. It was the dead of winter, and the outside seemed to me nothing but ice; I was stranded. At first it was difficult to read because the painkillers made me drowsy, and it was too physically difficult to write. So I watched a lot of TV and movies. One morning I was in the middle of A View to a Kill when I lost my sense of humor. The awfulness of the film could not be redeemed by the 80’s fashions or Christopher Walken or Grace Jones. A severe intestinal reaction to my medication kicked in. I paused the film over and over again, stumbling off to the bathroom. A View to a Kill threatened to kill me.

To escape, I started thinking about the troubled continuity of the James Bond films, and my thoughts fixated on my favorite of the series, 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, which offered more continuity troubles than any of them. This was the film in which the lead actor was replaced for the very first time: George Lazenby was the new Bond. At the end of the pre-titles sequence – a fistfight on a beach in which Bond doesn’t get the girl – Lazenby turns to the camera, breaking the fourth wall, and says, “This never happened to the other fellow.” It’s a winking moment which is basically saying, “Look, we all miss Sean Connery. I’m not Sean Connery. Now just sit back and we’ll have a good time, okay?” Or, perhaps: “Give me a chance, I beg you.”

Soon enough we’re in London, and Bond turns in his resignation. He heads to his office and cleans out his desk, encoutering a number of mementos from previous adventures, while composer John Barry plays snippets on the soundtrack from the respective films. It’s a cute, nostalgic moment, but wait a minute – I thought he wasn’t that other fellow? Even more confusingly, when he meets Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Telly Savalas) later in the film, Blofeld doesn’t recognize him, even though they previous tangled in You Only Live Twice. (The film backs itself into this corner by choosing to be a faithful adaptation of Ian Fleming’s novel OHMSS. In the novel, Blofeld and Bond are encountering each other for the first time.)

One popular theory is that “James Bond” is only a code name, so the various actors playing him are just agents accepting the 007 number, like football players donning a jersey. But why does Blofeld change his face, switching from Donald Pleasence to Telly Savalas? Is “Blofeld” just a code name too, something SPECTRE uses for its No.1? Most of all – why would this 007 be nostalgic for mementos of the former 007? How can nostalgia be transferred from one persona to another?

To arrive at a binding theory I needed Philip K. Dick.

I grew up on Philip K. Dick, encountering him first in junior high, when I read Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – coming to it through my interest in Blade Runner. What I got was something unexpected: not an expansion of the film, but a completely different story. It also made me feel something – melancholy. Empathy. Confused and unsettled (could it be that I was encountering literature for the first time?), I moved on to other Dick novels: Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said. Martian Time-Slip. Dr. Bloodmoney. Clans of the Alphane Moon. Time Out of Joint. Eye in the Sky. UBIK. Confessions of a Crap Artist. And on and on. At the time, a lot of Dick’s novels were out of print, and since eBay didn’t exist yet, being a PKD fan meant embarking on a treasure hunt in used bookstores from city to city. I kept reading PKD through high school, and then through college and grad school. He taught me that great speculative fiction was more than just delivering a high concept. Mars could be pretty much like suburban California: even with androids and flying cars, marriages could still fall apart, prejudice could still operate with malevolence, drugs consumed to escape reality.

At a Sarah Vowell signing for her book Assassination Vacation, I told her I liked that she included a passage from PKD’s We Can Build You. “It’s about the Abe Lincoln robot. What’s interesting is that he’s so sympathetic,” I said. “Yeah,” she said. “Way more sympathetic than the John Wilkes Booth robot.”

* * *

My story “Walther PKD” begins with a James Bond-type arriving in Santa Venetia late at night with the intention to assassinate a struggling science fiction author. The author has been targeted by the British Secret Service as a threat, for mysterious reasons. Our narrator, the assassin, has to sort out just why.

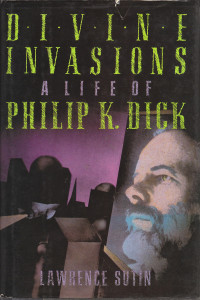

In writing this story I had to bluff myself. The very concept was silly, possibly of interest only to James Bond or PKD fans, and borderline fan-fiction. I had to ignore all of that, sit down and write it to see what it actually was. First I pulled off the shelf Lawrence Sutin’s seminal biography of PKD, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. I was trying to find the right moment in PKD’s life, and was thinking it should approximately take place during the Scanner Darkly period. I grabbed a few choice details for my “alternate” PKD, a different science fiction author living in California in the 70’s. I also looked at passages from Anne R. Dick’s The Search for Philip K. Dick and her descriptions of PKD’s drug intake at the time, juggling prescriptions from multiple doctors. I found a photo of his house in Santa Venetia on Google (my interior was largely imagined, apart from choice details, such as milkshakes in the fridge and classical music on the record player). The rest of the PKD stuff just came from years and years of reading him. Even though he died when I was just a tyke, he always felt like a mentor. (Fans often call him “Phil.”) His books helped teach me to write, but he also taught me how to think.

In writing this story I had to bluff myself. The very concept was silly, possibly of interest only to James Bond or PKD fans, and borderline fan-fiction. I had to ignore all of that, sit down and write it to see what it actually was. First I pulled off the shelf Lawrence Sutin’s seminal biography of PKD, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. I was trying to find the right moment in PKD’s life, and was thinking it should approximately take place during the Scanner Darkly period. I grabbed a few choice details for my “alternate” PKD, a different science fiction author living in California in the 70’s. I also looked at passages from Anne R. Dick’s The Search for Philip K. Dick and her descriptions of PKD’s drug intake at the time, juggling prescriptions from multiple doctors. I found a photo of his house in Santa Venetia on Google (my interior was largely imagined, apart from choice details, such as milkshakes in the fridge and classical music on the record player). The rest of the PKD stuff just came from years and years of reading him. Even though he died when I was just a tyke, he always felt like a mentor. (Fans often call him “Phil.”) His books helped teach me to write, but he also taught me how to think.

There are a few in-jokes. The “dark haired girl” is a nod to his famous infatuation with them (I have a book on my shelf of essays by Dick called The Dark Haired Girl.) Though no PKD works are name-checked, Time Out of Joint is obliquely referenced: the idea of objects being replaced by pieces of paper signifying them. His short story “The Electric Ant” plays a key role as well.

I also re-read some passages from Dr. No, Moonraker, and Live and Let Die to remind myself of Fleming’s voice. Even though my subject was the James Bond films, since the Bond-like character was the narrator, it seemed logical to go back to the source material. The rest was mimicry, largely. My editor Lee P. Hogg pointed out that the holster which my protagonist uses for his Walther PPK was actually made for revolvers, not pistols. I’d taken the detail from Fleming, but a search online revealed that this was Fleming’s mistake. I swapped it out for a more appropriate WWII-era German AKAH (Albrecht Kind) holster, fixing Fleming (gulp) but also aligning with the SF author’s implied condemnation of my protagonist as borderline Nazi – shades of Man in the High Castle. (My wife suggested I point out in the story that the secret agent is carrying the wrong kind of holster, but things were already getting pretty meta, and this joke was too obscure even by my standards.)

In embarking on this little What If, most surprising to me was the tone that emerged. I expected it to be a comedy. It’s not. There’s a sort of tragic feeling, a wistfulness, a melancholy – a broth composed of equal parts Fleming and PKD, though in the aftertaste I think PKD dominates slightly. It’s an experiment, and admittedly the peculiar taste may not be for everyone, but you can judge for yourself: it’s available now via The Singularity Magazine No. 1.